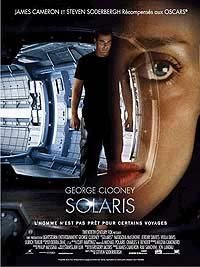

Solaris |

• Directed by: Steven Soderbergh. • Starring: George Clooney, Natascha McElhone, Viola Davis, Jeremy Davies, Ulrich Tukur, John Cho, Morgan Rusler, Shane Skelton, Donna Kimball, Michael Ensign, Elpidia Carrillo, Kent Faulcon, Lauren Cohn. • Music by: Cliff Martinez. • Directed by: Steven Soderbergh. • Starring: George Clooney, Natascha McElhone, Viola Davis, Jeremy Davies, Ulrich Tukur, John Cho, Morgan Rusler, Shane Skelton, Donna Kimball, Michael Ensign, Elpidia Carrillo, Kent Faulcon, Lauren Cohn. • Music by: Cliff Martinez.      A psychologist still reeling from the death of his wife receives a cryptic message from a friend telling him to join him on the space station Solaris which is studying a spatial phenomena. Because of the phenomena, people from the Solaris' crew's memories begin appearing and interacting with them, including the psychologist's dead wife. The people appearing do not know they were created by the phenomena and think they are the ''real'' people interacting with the people they know on Solaris. A psychologist still reeling from the death of his wife receives a cryptic message from a friend telling him to join him on the space station Solaris which is studying a spatial phenomena. Because of the phenomena, people from the Solaris' crew's memories begin appearing and interacting with them, including the psychologist's dead wife. The people appearing do not know they were created by the phenomena and think they are the ''real'' people interacting with the people they know on Solaris.

|

Trailers:

| Length: | Languages: | Subtitles: |

Review:

Kelvin travels to his destination via a ship called the Prometheus, a name associated with civilisation and enlightenment in Greek mythology. Once the Prometheus arrives at Solaris, however, Kelvin finds its inhabitants lost in terror, madness and confusion. Some have killed themselves, others have sequestered themselves in their cabins. All have seen facsimiles of people they once knew on earth, each seemingly conjured to life by the alien creature below. Kelvin sees his long-dead wife.

Lem is known for a number of "pessimistic" first contact novels. In "Solaris", his research station is populated by scientists who study the alien below using a scientific discipline known as Solaristics. They categorise, record and observe, but their mountains of data reveal no patterns and yield no insights. Rare for science fiction, Lem's alien thus remains resolutely "alien", impenetrable, inconversable and seemingly unknowable. Faced with epistemological limits, and a science which provides no answers, the researchers grow further insane. "We don't want other worlds," they growl, recognising that no man desires anything truly alien, "we want mirrors!"

As Lem's novel progresses, it becomes increasingly Kafkaesque. His humans become unhinged, disillusioned, at the mercy of forces that boggle the mind. Shockingly, they begin to doubt even their ability to understand human beings. "How can we expect to communicate with the ocean," they moan, "when we can't even understand one another?!"

It quickly becomes clear that Lem's alien is in fact experimenting upon his human characters. These experiments come from an omniscient being whose behaviour "makes no sense" and whose tests are inescapable. While it gathers data, mankind remains in the dark. While it pokes and prods, man's similar efforts yield nothing. And all the while, Solaris' oceans churn, man's anxieties and presuppositions reflected back up at him.

Andrei Tarkovsky adapted "Solaris" in 1972. His film ejects most of Lem's science, skirts over Lem's interest in exobiology, and instead focuses on Kelvin's relationship with his "reincarnated" lover. It then climaxes with Kelvin accepting this facsimile as a fraud, but nevertheless making the decision to spend the rest of his life with it. The film's final sequence finds Kelvin travelling down to Solaris, and living on a simulated island with his simulated lover.

Tarkovsky's film demonstrated a strong, anti-technology bias. It is filled with characters who bemoan machines and space-travel, all of which distract from some supposedly deeper "spiritual" and "material" reality. Tarkovsky then offers "nostalgia" (for love, life, flesh and earth) as a force which humanity cannot live without. Tarkovsky doesn't glorify "nostalgia" - his Earth is nevertheless one of decay, loneliness and inhospitable Russian winters -' but he nevertheless presents it as something markedly better than the cold churches of science, which promise everything but deliver little. That this is a false binary doesn't occur to Tarkovsky.

Tarkovsky, a Christian, also manages to turn his adaptation into a darkly religious parable. His Kelvin takes a "leap of faith" and chooses to believe in a paradise on the surface of Solaris in which the deceased now roam free. All these changes, of course, infuriated Lem, who detested Tarkovsky's adaptation. "He didn't make Solaris, he made 'Crime and Punishment'," Lem fumed. "The book was not dedicated to the erotic problems of people in outer space! I wanted to create a vision of a human encounter with something that cannot be reduced to human concepts, ideas or images! This is why the book was entitled 'Solaris' and not 'Love in Outer Space'!"

Elsewhere Lem would accuse Tarkovsky of misinterpreting his novel. For Lem, the facsimiles created by the aliens were, quote, "exemplifications of certain concepts derived from Kant; the Unreachable, the Thing-in-Itself, the Other Side which cannot be penetrated! The whole sphere of cognitive and epistemological considerations was extremely important in my book and it was tightly coupled to the solaristic literature and to the essence of solaristics as such. But the film has been thoroughly robbed of those qualities!" In short, Lem was upset that Tarkovsky's adaptation was not preoccupied with "alienness", but with what Lem called "Kelvin's pangs of conscience"; human characters who essentially use aliens to assuage past regrets.

Steven Soderbergh adapted Lem's novel in 2002. Slick and brisk, the film replaces Lem's roiling oceans with a planet shrouded in what resemble flickering synapses and frayed nerve-endings. Like Tarkovsky, Soderbergh ignores Lem, and focuses primarily on Kelvin's nostalgic longings for his lost lover. Elsewhere Soderbergh's aliens never rise above other cinematic creatures skilled at bringing human thoughtsmemories to life ("Forbidden Planet", "Sphere" etc).

Bizarrely, Soderbergh's adaptation has even more "religious" veins than Tarkovsky's. Soderbergh's Kelvin is an atheist who nevertheless adores Dylan Thomas' "And Death Shall Have No Dominion", a poem based on the New Testament. According to the poem, faithful men make it to the Kingdom of Heaven, faith in Christ assuring salvation. In the film's final act, Kelvin is himself called upon to make a choice: flee his exploding space station or remain behind and perish in the hope of being reunited with his lover. Kelvin remains faithful and is granted a meeting with an angelic kid. This kid touches Kelvin's hand, echoing Michaelangelo's The Creation of Adam", at which point Kelvin is granted eternal afterlife. Like Tarkovsky, Soderbergh thus delivers the opposite of Lem. For both directors, something alien and incomprehensible is confronted, which swiftly proceeds to quench Earthly longings, beliefs and Western spiritual traditions. Even in deep space, ET essentially gives the audience what it wants.

Review by tieman64 from the Internet Movie Database.

Off-Site Reviews:

Nov 28 2017, 14:31

Nov 28 2017, 14:28

Movie Database