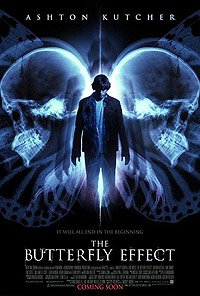

Butterfly Effect, The |

• Directed by: Eric Bress, J. Mackye Gruber. • Starring: Ashton Kutcher, Melora Walters, Amy Smart, Elden Henson, William Lee Scott, John Patrick Amedori, Irina Gorovaia, Kevin G. Schmidt, Jesse James, Logan Lerman, Sarah Widdows, Jake Kaese, Cameron Bright. • Music by: Mike Suby. • Directed by: Eric Bress, J. Mackye Gruber. • Starring: Ashton Kutcher, Melora Walters, Amy Smart, Elden Henson, William Lee Scott, John Patrick Amedori, Irina Gorovaia, Kevin G. Schmidt, Jesse James, Logan Lerman, Sarah Widdows, Jake Kaese, Cameron Bright. • Music by: Mike Suby.      Evan Treborn wants to free himself from his disturbing childhood memories. As a kid, he often blacked out for long periods of time and tried to detail his life in a journal. As a young adult, he revisits the journal entries to figure out the truth about his troubled childhood friends Kayleigh, Lenny, and Tommy. When he discovers he can travel back in time in order to set things right, he tries to save his beloved friends. However, he finds out that relatively minor changes can make major problems for the future. Evan Treborn wants to free himself from his disturbing childhood memories. As a kid, he often blacked out for long periods of time and tried to detail his life in a journal. As a young adult, he revisits the journal entries to figure out the truth about his troubled childhood friends Kayleigh, Lenny, and Tommy. When he discovers he can travel back in time in order to set things right, he tries to save his beloved friends. However, he finds out that relatively minor changes can make major problems for the future.

|

Trailers:

| Length: | Languages: | Subtitles: |

Review:

Intriguingly enough the tone changes after Evan has his first breakthrough - to call it that - in visiting his past and altering the events his black-outs shrouded: now, instead of being a shy, bit nerd college student, is wearing the clothes of an a-male student, all testosterone, Greek alphabet community AND he also has the girl of his childhood and dreams. But the bad brother of hers we witnessed early on, and the responsible for many of the kids' troubles, re-enters the frame. And here things start to get interesting.

No matter what Evan does, the roller-coaster of memories, facts and rehabilitation of traumas he embarks on is always out of complete control: no matter what he does, there is always a little left-over that troubles things and arguably makes matters worse, and that little piece always sneaking out, always being a left-over, is nothing else but the Real, courtesy of lacanian psychoanalysis. It actually fits one of the possible definitions of that hard to grasp thing: the Real is the Impossible. It is crucial here to differentiate reality, what we call everyday reality, from the Real: the Real is that hard kernel Evan is about and is always left out from our everyday, symbolic reality, governed by rules, laws, language. And the film is a good vehicle to illustrate that.

It is also a good vehicle against the kind of rehabilitation books like "Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus" try to establish; some time back, its author, invited by Oprah Winfrey on her show, proposed the theory that no matter how traumatic an event can be, we can really go back and visit it and alter it! A participant agreed to be put to the test via hypnosis, and was relieved afterwards because she could finally go back and visit a traumatic scene with her father, change it, and forgive her father, and live happily ever after. So, to repeat the ridicule of this phenomenon by the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek: if the primordial scene (that is the scene none of us could have witnessed, and yet the one that is the playground, to put it that way, of our fantasies, the scene of parental intercourse for our conception) is too traumatic, why, you can always alter it: you can have mother knitting, and father reading his newspaper...

So, to go back to the film: after the first dramatic change of events, by revisiting the past and changing all that, I think it shrewdly ridicules the standardization of American healthiness: if you can have mom knitting and father reading his newspaper instead of some dramatic event, why, then you can have the girl of your dreams, power over new weaklings, AND be an a-male. Not even "Heathers" have accomplished it so ferociously. And subtly.

From then on, the film spins into ever more pessimistic loops, and Evan finally has to confront his madness, the madness of always trying to alter events - by acting them out, finally. No wonder this tactic, if Evan - or we, for that matter - wants to clean the slate clean, has to start by sweeping clean all preconceptions of the love-object, of any kind of 'intimate' knowledge we have of the other.

No wonder also, when that happens, when he actually tells Kayleigh about all those alternate "universes" he has knowledge of and of "her" past, she is a beat-down love-object who has to reject him: telling her that he saved her from molestation in that other universe, but not from evil-doings in this one, is a male fantasy that appropriately disgusts her. There is always a distance from fantasy and guilt to where the other stands, and makes finally desire operative.

This is I think where the film fails. Apparently there are four versions for ending this film, the three alternate coming with the DVD. The director's cut ending is gruesome and stupid: baby Evan "revisits" its birth and strangles itself, as if the loop of guilt has to strangle itself in the end. The open ending is a slight variant of the end appearing in the theatrical version, that is Evan hesitates but follows her. But if there was an instance where the happy ending would be totally legitimate is this happy ending: he goes over and asks her out! Why didn't they choose this? It makes perfect sense. When I mentioned before her run-down "version" as an amorous object, there is something crucial that also happens the first time Evan visits Kayleigh as a young man: she may be in difficult situations, yet she asserts herself and her desire, while he does not, as if he was always entrapped in the vicious circle of sacrifice and redemption, so he cannot face her, because this would arguably endanger her. This is all very fine, tuned to the Immaculate Lady theme of the Trobadours, but our semi-hero Evan has still to know what love is: as it is he remains frail as a butterfly, without fully assuming the chaotic power of love.

Review by sandover from the Internet Movie Database.

Movie Database