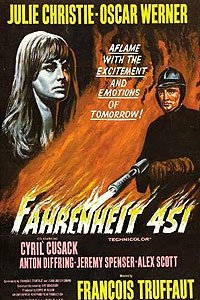

Fahrenheit 451 |

UK • 1966 • 112m •

• Directed by: François Truffaut. • Starring: Julie Christie, Oskar Werner, Cyril Cusack, Anton Diffring, Jeremy Spenser, Bee Duffell, Alex Scott, Gillian Aldam, Michael Balfour, Ann Bell, Yvonne Blake, Arthur Cox, Frank Cox. • Music by: Bernard Herrmann. • Directed by: François Truffaut. • Starring: Julie Christie, Oskar Werner, Cyril Cusack, Anton Diffring, Jeremy Spenser, Bee Duffell, Alex Scott, Gillian Aldam, Michael Balfour, Ann Bell, Yvonne Blake, Arthur Cox, Frank Cox. • Music by: Bernard Herrmann.      Guy Montag is a firefighter who lives in a lonely, isolated society where books have been outlawed by a government fearing an independent-thinking public. It is the duty of firefighters to burn any books on sight or said collections that have been reported by informants. People in this society including Montag's wife are drugged into compliancy and get their information from wall-length television screens. After Montag falls in love with book-hoarding Clarisse, he begins to read confiscated books. It is through this relationship that he begins to question the government's motives behind book-burning. Montag is soon found out, and he must decide whether to return to his job or run away knowing full well the consequences that he could face if captured. Guy Montag is a firefighter who lives in a lonely, isolated society where books have been outlawed by a government fearing an independent-thinking public. It is the duty of firefighters to burn any books on sight or said collections that have been reported by informants. People in this society including Montag's wife are drugged into compliancy and get their information from wall-length television screens. After Montag falls in love with book-hoarding Clarisse, he begins to read confiscated books. It is through this relationship that he begins to question the government's motives behind book-burning. Montag is soon found out, and he must decide whether to return to his job or run away knowing full well the consequences that he could face if captured.

|

Trailers:

| Length: | Languages: | Subtitles: |

Review:

Guy Montag, his name recalling a character in Kafka's "The Trial", is one such book burner, though he also lives a secret life in which he passionately reads books. Gradually these book awaken Guy's curiosity. Around him, everyone's popping pills, watching reality TV, interacting with interactive media and living in a daze (Bradbury's novel is said to have even predicted the invention of the Ipod or Walkman). Surely, Guy thinks, books are a means of fleeing this dreary reality? A means of provoking some form of change? Surely.

From here on, "books" become Bradbury's blunt metaphor for any and all "knowledge". But this is a knowledge less suppressed by the state than it is rejected (made clearer in Bradbury's novel) by a hedonistic populace which instead seeks incessant pleasure. In other words, the books are not ignored because they are burnt, but are burnt because they are ignored.

Late in the film, the authorities learn of Guy's book reading transgressions. Like Antoine in Truffaut's "The 400 Blows", Guy thus flees, escaping to the woods where he finds a rebel faction in hiding. Here, each person has committed a different book to memory. They are the guardians of knowledge, the elite minority who preserve texts which have otherwise been lost.

Like Bradbury's novel, Truffaut's film is implicitly about the post-literate generation and the death of books at the hands of New Media (the television, the cinema etc). The film begins with television antennas, text-less opening credits, the alternating colours of the visible light spectrum (or old cathode tubes) and features books being literally swallowed by TV sets. The "fire engine" of the book burners is itself a Hollywood mobile camera crane/truck. What the film thus charters is man's transition into the post-literate age and the death of both orality and literature. Like Bradbury's future, our Western present is one of criss-crossing multimedia. Writing and reading are still of value, but only in so far as they facilitate the manipulation of other media. The post-literate society assumes traditional literacy skills, but the typical post-literate is a passive literate. Books are read, provided they are snappy, hook dwindling attention spans or plug directly back into New Media, either via form (ebooks, ipads) or content (celebrity, actor biographies etc).

Mentioned also in Bradbury's novel, but not the film, is the idea of a rise in "noncombustible data", a term Bradbury used to refer to an increase in any information that is incapable of producing reflection, analysis, contemplation, comparison, and/or an understanding of how a political, social, or economic system works. What Bradbury essentially predicted was the information age, an age in which everything is accessible, but the sheer volume of information, both junk and otherwise, not only makes fishing a burden, but precludes the need to find, master or apply this information.

Truffaut's film was ignored upon release and today still has a poor reputation. This is largely because Truffaut revokes your typical science fiction aesthetic, and instead channels, firstly, the retro aesthetics and production design work of 1950s "classic" Hollywood scifi (see "Forbidden Planet"), and secondly, early 50s Hitchcockian opera. Indeed, "Fahrenheit" is one giant love letter to Alfred Hitchcock - of whom Truffaut would publish a book on a year later - with its pounding Bernard Herrmann score, gigantic emotions, sweeping orchestrations, snappy cutting, bold colours, "Spellbound" inspired dream sequences, 360 degree spins and punchy, whiplash-like camera work. In addition to this, actress Julie Christie plays a pair of double roles (like Kim Novak in "Vertigo") and actor Oskar Werner becomes your typical Hitchcockian running man (as an Austrian outsider who hid from the Nazis, Oskar's real life echoes Truffaut's film). Truffaut even films some sequences backwards, to give the film a dreamy, surreal edge.

So at its best, Truffaut channels the baroque, bombastic tone of Hitchcock, which is why "Farenheit" tends to be liked only by those intimately familiar with directors like Hitchcock or Brian De Palma. Like "Fahrenheit", Hitchcock's later films and De Palma's own oeuvre are similarly shunned. There is a perception that this aesthetic style -' expressionistic, dreamy, operatic -' belongs solely to a naive era of cinema. It can not slip past the late 60s. Today's rise in rationalism and the corresponding rise in insincerity negates Hitchcock's brand of deadpan, sincere expressionism.

Though prophetic, Bradbury got two big things wrong. The intellectualism and bookishness that he celebrates was always marginal and elitist. The post literate society simply forces this elitism to take a different shape. His big mistake, though, was in assuming that a future state would ban all art. Today's reality is not the barren, censored, repressed world of Bradbury, but the cultural overload, media-saturation and hyper-hedonism of "A Clockwork Orange". Put art everywhere, give it to everyone, commodify everything and everybody, and you effectively neutralise art, books, objects and people. This is what German philosopher Herbert Marcuse, in his book "One Dimensional Man", called "repressive desublimation". Marcuse saw that postmodern capitalism had "internalised" Marxism and would increasingly resemble a perverse hybrid of Soviet-style totalitarianism and US-style consumerism. In this world, commodities, art and objects are not just a means of distraction, but the "Ideology" itself. In short, in a world where nothing is repressed, where certain forms of desublimation (freedom) are encouraged, and where everything theoretically can be yours, attention is drawn away from the oppressive and authoritarian character of society, and there becomes no practical grounds for rebellion. Meanwhile, books are everywhere, but nobody reads them.

Review by Scott Amundsen [IMDB 20 July 2011] from the Internet Movie Database.

Movie Database