Ghost of Frankenstein, The |

USA • 1942 • 67m •

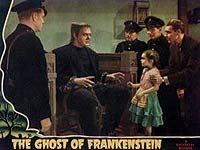

• Directed by: Erle C. Kenton. • Starring: Lon Chaney Jr., Cedric Hardwicke, Ralph Bellamy, Lionel Atwill, Bela Lugosi, Evelyn Ankers, Janet Ann Gallow, Barton Yarborough, Doris Lloyd, Leyland Hodgson, Olaf Hytten, Holmes Herbert, Richard Alexander. • Music by: Hans J. Salter. • Directed by: Erle C. Kenton. • Starring: Lon Chaney Jr., Cedric Hardwicke, Ralph Bellamy, Lionel Atwill, Bela Lugosi, Evelyn Ankers, Janet Ann Gallow, Barton Yarborough, Doris Lloyd, Leyland Hodgson, Olaf Hytten, Holmes Herbert, Richard Alexander. • Music by: Hans J. Salter.      Ygor resurrects Frankenstein's monster and brings him to the original doctor's son, Ludwig, for help. Ludwig, obsessed with the idea of restoring the monster to full power, is unaware that his various associates all have different ideas about whose brain is to be transplanted into the monster's skull. Ygor resurrects Frankenstein's monster and brings him to the original doctor's son, Ludwig, for help. Ludwig, obsessed with the idea of restoring the monster to full power, is unaware that his various associates all have different ideas about whose brain is to be transplanted into the monster's skull.

|

Trailers:

| Length: | Languages: | Subtitles: |

Review:

Series note: Because the Frankenstein films to this point are as chapters in a novel, it's advisable that you watch them in order. Begin with Frankenstein (1931), The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939), and then finally this film.

As the first three Frankenstein films are all 10s in my view, The Ghost of Frankenstein is a slight letdown. It's still a good film, but the atmosphere isn't quite as creepy, the sets aren't quite as good, the acting is cheesier (especially from Lugosi, who was already mired in serious off-camera personal problems by this point), and the scant running time doesn't help the film develop as well as it should.

Despite the problems, there is much to admire. Director Erle C. Kenton, who began his long career during the silent era, appearing first as an actor in 1915, still gives us nods to the expressionist elements of the previous films. A scene that takes place on rooftops is probably the most direct reference in the series to the production design of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari, 1920). Kenton also references the other Frankenstein films without mimicking them--such as the scene where the Monster appears outside of the heroine's window, or the flashback sequence, which at first might feel like padding, but turns out to be necessary on examination.

Vasaria is just as attractive as the elaborately realized village of Frankenstein in James Whale's films. Ludwig's palatial home, though more contemporary looking--the series continues through this point to modernize its mostly anachronistic settings--is still impressive, even if it can't match the amazing, towering-behemoth sets of the castle. Kenton's interesting point-of-view shots of our new Monster, Lon Chaney Jr., emphasize his hulking size (Chaney was 6 foot 3 and bulky) so that it looks like the sulfur pit was not only rejuvenating but cultivating for the formerly Karloffian Monster.

The look for The Ghost of Frankenstein is much brighter than the previous films. There aren't such deep shadows, the sets are better lit and appear a bit "crisper". For me, while this loses some of the atmosphere, it's attractive for different reasons. The music, a combination of an original score by Hans J. Salter and stock music by Charles Previn, is interesting, particularly for its occasional resemblance (although more traditionally tonal) to Stravinsky's Petrushka (originally written in 1911).

Kenton and writers Scott Darling and Eric Taylor gave this entry a poignant spin by creating what is essentially a discourse on appearance differences, such as ethnic or subcultural identities. The Monster seems to be despised and feared not so much because he is evil but because he is the proverbial Other. He looks different, walks different, and "talks" different; it is because of this that he is considered a monster. While technically, he does commit crimes, they tend to be precipitated by dehumanizing, often violent reactions from the people around him. That's why the Monster has positive relationships with children--the idea is that they have not yet been socialized into dehumanizing the Other. Instead they have positive, curious reactions to him, which he reciprocates. Of course, these subtexts are present in all of the Frankenstein films, but Kenton, Darling and Taylor make it much more overt here. When Ludwig and his assistant are debating dissection of the monster to destroy him, we even get this line of dialogue, "How can you call the removal of a thing that is not human 'murder'?" The Monster is certainly human--he's made only of human parts. But regardless, because of difference, he is dehumanized conceptually, and thus a candidate for relatively casual extinction.

The resolution that Kenton, Darling and Taylor show for the characters in the film dealing with the Other is also informative. To our "heroes", the best answer seems to be physically manipulating him, to a severe extent--it would cause the Monster to lose his personal identity. The goal isn't acceptance of the Other, but molding the Other to be the same as they are.

While this is certainly not the best entry in the series, it's a must-see, as it provides important links in Universal's Frankenstein mythos, which was continued for four more films.

Review by Brandt Sponseller from the Internet Movie Database.

Movie Database