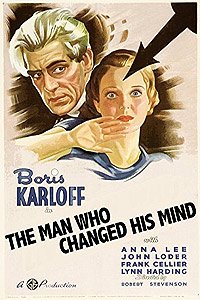

Man Who Changed His Mind, The |

|

UK • 1936 • 66m •

• Directed by: Robert Stevenson. • Starring: Boris Karloff, John Loder, Anna Lee, Frank Cellier, Donald Calthrop, Cecil Parker, Lyn Harding, Clive Morton, Bryan Powley, D.J. Williams. • Music by: Hubert Bath. • Directed by: Robert Stevenson. • Starring: Boris Karloff, John Loder, Anna Lee, Frank Cellier, Donald Calthrop, Cecil Parker, Lyn Harding, Clive Morton, Bryan Powley, D.J. Williams. • Music by: Hubert Bath.      Dr. Laurience, a once-respectable scientist, begins to research the origin of the mind and the soul. The science community rejects him, and he risks losing everything for which he has worked. He begins to use his discoveries to save his research and further his own causes, thereby becoming... a Mad Scientist, almost unstoppable... Dr. Laurience, a once-respectable scientist, begins to research the origin of the mind and the soul. The science community rejects him, and he risks losing everything for which he has worked. He begins to use his discoveries to save his research and further his own causes, thereby becoming... a Mad Scientist, almost unstoppable...

|

Review:

Karloff is Dr. Laurience, a well known neuroscientist who had a reputation for being brilliant but whom we learn has developed a reputation as an off-his-rocker quack in the last few years. As The Man Who Changed His Mind opens, we meet the charming young Dr. Clare Wyatt (Anna Lee). A colleague says that this is the last time he will be working with Wyatt. We learn that she is heading off to be Laurience's research assistant. Everyone warns her not to go, especially Wyatt's boyfriendfiancé-hopeful Dick Haslewood (John Loder), a budding reporter who works for the newspapers owned by his father, Lord Haslewood (Frank Cellier).

Wyatt is determined and a bit stubborn. She heads off to Laurience's manor while basically forbidding Haslewood to go along. He follows anyway. Wyatt soon learns why Laurience has a questionable reputation--he's been experimenting with siphoning off the mind, or the "soul", as he calls it, from monkeys by using sophisticated scientific equipment. Now that Wyatt has arrived and Laurience finally has a capable, trustworthy assistant, he plans on experimenting with two monkeys in an attempt to swap their minds. If that goes well, he says he is going to try the same with humans. Wyatt is disturbed by this, claiming it is highly unethical. But when Lord Haslewood offers financial backing for an exclusive (including copyright ownership) on Laurience's published results, Laurience has the facilities he needs to accelerate his goals. What will be the result of the experiments?

Director Robert Stevenson, whose career interestingly went from hard-boiled genre films to serious dramas before he finally settled into almost exclusively directing live-action Disney classics throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, engenders a thematic and atmospheric kinship to the early 1930s Universal horror classics in the earliest moments of The Man Who Changed His Mind. Thematically, we're first deposited in a clinical, respectable "high science" environment, before our hero(ine) makes a journey to a distant land, first via train, then by coach (which is characteristically driven by someone afraid to complete the journey) to a dingy, Gothic mansion to meet the antagonist. The antagonist has that role more by a compelled disposition than by choice. The journey signifies the transition between a cheery contemporary public façade for scientific endeavors and the "nasty truth" underlying the obsession with the current outgrowth of technology--that it is rooted in the mysterious, dangerous and uncouth "magic" of the alchemists. The mad scientist is in the role of the obsessed alchemist, of course, foolishly toying with God's creations in what amounts to a Satanic bid to become God himself. This is the well-known ideological basis of Dr. Frankenstein, and Stevenson carries it over to the present film.

Interestingly, the trio of screenwriters included John L. Balderston, who not only co-wrote Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, but also the play that formed the basis of Dracula (1931), Universal's first sound horror film of the Gothic era. Dracula features a similar journey at the beginning, even if the surface mechanisms involved in the conflict there are not scientific, but bureaucratic, centering on a real estate deal.

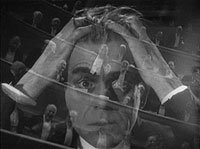

The Man Who Changed His Mind, like the Frankenstein films, uses "gobbledy-gooky" contraptions to fuel its bizarre metaphysics. Also like Frankenstein, the basic principle involved is electricity. In fact, The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) even has a similar plot device to this film, even if it's not so much the focus there. Laurience's motivation here may be more selfish than Dr. Frankenstein's--he's ultimately trying to find a way to prolong his own life, but this make him no less dangerous as an antagonist.

Balderston and his co-writers Sidney Gilliat and L. du Garde Peach also go a bit further in trying to get at difficult scientific and philosophical issues here concerning "what is mind?" Of course, they can't quite give an answer, but that's not surprising, as a few hundred years of work from philosophers, psychologists, neuroscientists and such hasn't exactly provided an answer yet, either. Because of this, and for other ex-positional reasons, The Man Who Changed His Mind sometimes has very fast, "thick" dialogue (this is probably exacerbated by the 60-some minute running time, as well), but the dialogue never becomes burdensome. Audiences in this era were expected to be quicker and more intelligent. It's quite refreshing. The script also has more biting humor than one might expect, but you have to listen closely to make sure you do not miss some of the odder and more scathing jokes.

As it is heavy on dialogue and light on environment changes and things like special effects (aside from the Frankenstein devices), films like this must ultimately succeed or fail on the performances. Karloff is entrancing, complex and convincingly obsessive, even if he's not exactly playing the kind of guy you'd like to take out for a few beers. Lee is a delight as a headstrong, intelligent, powerful woman--especially given that this wasn't the norm for genre films of the era. Donald Calthrop is excellent as a feisty quadriplegic, and Cellier does a fantastic job in a demanding role that requires drastic changes of character.

If there's a flaw, it's merely that the short running time makes the film feel a bit lighter than it should. But Karloff fans and any fans of genre films of this era can't afford to miss this one.

Review by BrandtSponseller from the Internet Movie Database.

Off-Site Reviews:

Movie Database