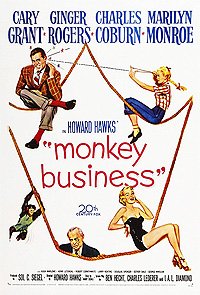

Monkey Business |

|

USA • 1952 • 97m •

• Directed by: Howard Hawks. • Starring: Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Charles Coburn, Marilyn Monroe, Hugh Marlowe, Henri Letondal, Robert Cornthwaite, Larry Keating, Douglas Spencer, Esther Dale, George Winslow, Charlotte Austin, Harry Bartell. • Music by: Leigh Harline. • Directed by: Howard Hawks. • Starring: Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Charles Coburn, Marilyn Monroe, Hugh Marlowe, Henri Letondal, Robert Cornthwaite, Larry Keating, Douglas Spencer, Esther Dale, George Winslow, Charlotte Austin, Harry Bartell. • Music by: Leigh Harline.     Barnaby Fulton is a research chemist working on a fountain of youth pill for a chemical company. While trying a sample dose on himself, he accidentally gets a dose of a mixture added to the water cooler and believes his potion is what is working. The mixture temporarily causes him to feel and act like a teenager, including correcting his vision. When his wife gets a dose that is even larger, she regresses even further into her childhood. When an old boyfriend meets her in this state, he believes that her never wanting to see him again means a divorce and a chance for him. Barnaby Fulton is a research chemist working on a fountain of youth pill for a chemical company. While trying a sample dose on himself, he accidentally gets a dose of a mixture added to the water cooler and believes his potion is what is working. The mixture temporarily causes him to feel and act like a teenager, including correcting his vision. When his wife gets a dose that is even larger, she regresses even further into her childhood. When an old boyfriend meets her in this state, he believes that her never wanting to see him again means a divorce and a chance for him.

|

Trailers:

| Length: | Languages: | Subtitles: |

Review:

Sadly, the film itself offers a poignant metaphor for its construction: Grant's scientist, toiling away at his wonder drug, has all the right ingredients, but can't seem to cobble them together in a way to get the desired result. The film's script and editing feel rushed and piecemeal, with the film lurching between scene to scene with minimal cohesion, giving the impression the script was being constantly reworked on set (hardly an unusual practice in Classical Hollywood, but seldom this evident). Even the normally flawless Hawks flounders directorially, struggling to settle on a tone (zany or deadpan?), and settling on a languid, meandering pace that doesn't seem to fit the increasingly wacky mischief, making Grant and Rogers' youthful running wild feel oddly polite and strained.

This is not to say that all is lost: the script blurts out some audaciously risqué and clever one- liners here and there, and the central premise remains novel enough to yield comedic mileage aplenty. The antics of Grant and Rogers gleefully suffering the effects of his anti-aging serum do offer moments of exquisite comedic timing (Rogers' titter when surreptitiously sliding a goldfish down Charles Coburn's pants is a comedic sight gag for the ages). On the other hand, they also forcibly rub many particularly, cringe-worthily antiquated comedic bellyflops in the viewer's face. A scene of Ginger Rogers dismissing very founded allegations of spousal abuse played off as a joke? An excruciatingly long sequence of Grant, regressed to full- fledged boyhood, painting his face and "playing Injun", whoop-whoop-whooping and all? Yeesh. It's moments like these that make contemporary viewers leery of watching "old movies".

As the film ambles along to its madcap finale, Hawks finally hits his stride, delivering a climax of amiably memorable chaos, including Rogers mistaking her husband as having literally regressed into a baby, and a lab full of stuffy scientists, cackling, having a water fight while swinging from chandeliers. If the film as a whole had tapped into this same sense of energetic lunacy, Monkey Business might have lived up to its name. Instead, we conclude with a trite, disingenuous monologue about the benefits of age and maturity that feels so slapped on by the Hays Code the lens is practically clouded by the fingerprints of Joseph Breen. The audience subsequently departs feeling like the titular monkeys may have been left in charge of the editing suite.

It's hard to imagine a more appropriate actor to meld bumbling pomposity with youthful sprightliness than Cary Grant, but even the screwball king is not immune to the off-kilter feeling pervading the film. The film's opening, an inspired breach of the fourth wall, has Grant attempting to walk into the scene, halted by an offscreen voice (Hawks himself, in an odd cameo) intoning "Not yet, Cary", proves oddly prophetic, as Cary never appears to be fully present in a scene, delivering his perfectly precise zingers and customary tumbling in an oddly distant, disinterested manner. While it's true that Grant on autopilot is still a more capable comedian than most others at their best, the feeling that he's never really enjoying himself certainly doesn't help the audience do so. As such, it's left to Ginger Rogers to steal the show with a hugely commanding presence, sliding between heartwarmingly caring wife to mischievously destructive, pouty girl (and the only cast member to convincingly tap into the quirks and nuances of portraying a child). The early scenes of Rogers gently coaxing the absentminded Grant into remembering to leave through the door before locking it are practically awash with a warm glow, which is perfectly shattered by her later flopping on the floor, screeching with laughter, like a caffeine-addled salmon.

As support for the headliners, Charles Coburn maintains his reputation as cinema's best blusterer as Grant's hem-hemming CEO, and, though it's disappointing for Marilyn Monroe to have little to do other than suffer objectification jokes on her behalf, she still plays the wide- eyed airhead stereotype with as much class and coy timing as possible. Ultimately, however, the clear runaway star of the show is Esther the chimpanzee. The unfathomably choreographed scenes of her physical comedy interactions with the cast, and later sequences of her serenely mixing chemicals with a fluidity that would put Gene Kelly to shame, are the few moments where the film achieves an almost transcendent fascination, never to be seen in the loathsome subsequent 'animal humour' comedies polluting the 80s and onward.

While Monkey Business may fizzle rather than crackle considering the almost intimidating array of talent on display, there are still many throwaway bits where the stars momentarily align and offer comedic gold. Screwball fans willing to indulge the film's somewhat lumbering tempo and wince-worthy 'product of its time' breaches of political correctness will still find enough zaniness on display to cobble together a breezily enjoyable time. Otherwise, viewers with a more sensitive palate will find the film rather like its youth serum: rather bitter, and resulting in a fairly obnoxious and forgettable cacophony of adults who should know better.

Review by pyrocitor from the Internet Movie Database.

Movie Database